“There are always multiple ways to do the same thing, either well and also not quite so well. And perhaps it is not always necessarily how long, how often or how hard one climbs that weighs in at a greater value, but perhaps instead it is more so, the knowledge, skills, and experience one gains after each climb that counts for more than the actual climb itself.” –SAN LLC

PRACTICAL BASIC TECH TIPS:

To get notifications for upcoming SAN LLC TECH TIPS, join or like our SAN LLC FB here: https://www.facebook.com/SanirangAlpineNetworks/

05-01: Rope Cutting – Can’t Cut It…?

You just can’t seem to cut it after a long day of climbing and for some reason or another it has come to doing the almost unthinkable– cutting your own rope. This situation doesn’t come up often, and even less so if you are thoughtful, careful and skilled at pulling your rope and/or know how to resolve and retrieve a stuck rope safely. Our solutions on how or what to cut your rope with may not be the prettiest or cleanest methods, but they do the job and get you on your way. Here we go, from best to worst…and of course, the first option and/or any of the following options make the lower listed options obsolete, but fun to entertain the thought. Make it easier on yourself and buy a lightweight knife!

You just can’t seem to cut it after a long day of climbing and for some reason or another it has come to doing the almost unthinkable– cutting your own rope. This situation doesn’t come up often, and even less so if you are thoughtful, careful and skilled at pulling your rope and/or know how to resolve and retrieve a stuck rope safely. Our solutions on how or what to cut your rope with may not be the prettiest or cleanest methods, but they do the job and get you on your way. Here we go, from best to worst…and of course, the first option and/or any of the following options make the lower listed options obsolete, but fun to entertain the thought. Make it easier on yourself and buy a lightweight knife!

1. KNIFE: Not necessary, but worth having one to make a cleaner and quicker cut. It’s also good to have for cutting and dicing food and for the use of any of its additional accessory tools. Stringing it like a necklace tucked inside one’s shirt prevents the nuisance of bobbling, catching on stuff and possibly even strangulation. Keeping it strung around one’s neck with sufficient enough string/cordage to clear one’s helmet is beneficial amidst one’s climb; plus, with the string/cord can potentially be helpful for other uses

2. ICE PICK: The front point of the pick or top edge of a pick can be used as a blade to cut a rope with relative ease; however, on mixed terrain where the picks get blunted, keeping the top edge finely tuned is a bonus. The teeth of the picks, though not as clean, would likely also do the trick, too.

3. MINI FILE: Packing in a lightweight flat file(e.g. fishing hook file) also does a good job cutting the rope. Packing in a file is good for fine tuning picks on the go. They also pack easily and nicely with an assortment of potentially necessary mini tools in the event that crampon or axe needs to be adjusted or fixed amidst a long climb.

4. CRAMPONS: The obvious reason behind why stepping on the rope in crampons is a no-no also makes for a good way to cut the rope.

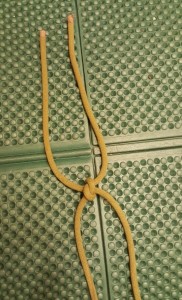

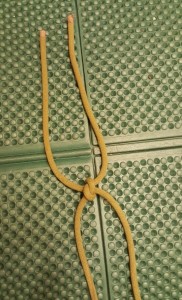

5. ICE SCREW: Threading the rope through the ice screw hole to the desired point and rotating the rope against the edge of the screw’s teeth work. It might take a while, but works. The Grivel wired swivel handle easiest since it can pinch down on the rope, fixing it in place which makes rotating the opposite rope end being cut easier.

6a. NUT PICK: Just thread the rope through one of the nut pick’s holes or gaps, place the rope between the pick and the rock, grab tight and rub away. Primitive, time consuming and desperate, but eventually… Some nut picks have knife blades integrated in them…which would bump this to the top of this list.

6b. WIRED STOPPER: Push the nut wire back through the nut in the opposite direction it is meant to be loaded in order to create a loop in which the rope may be threaded through and pinched into place by pulling and tightening the nut wire back. Grab the rope and wire and rub the rope against the rope while keeping the rope between the nut and rock wall. Of course, this technique won’t work with the lighter single wire stoppers.

6c. MID-SIZE+ CAM: Just as desperate and at the same level as the previous two(6a & 6b), thread the rope through a hole in the wing of a mid-sized cam and rub away!

6d: ALL OF THE…other ridiculous ways similar listed under 6…you could literally used anything from a carabiner to wrapping the rope arounda fist-sized rock and rubbing the rope up against the wall. If you become desperate enough, you’ll figure out how to cut the damned rope.

7. LIGHTER/BURNER: Either of these two will cut(melt!) a rope. Not higher on the list because burners are not only cumbersome, but can also be dangerously flamable before or while it’s priming along with the issues of keeping the flames clear of other gear while hanging at the station. The burner also consumes precious gas that might be needed for later(e.g. boiling water). Lighters may not have enough gas to burn through the rope. Both pose problems when it comes to their reliability to stay flamed in windy or wet conditions. However, both can help rope slippage at the cut end granted the cut was made cleanly.

NOTE: Always make sure to tie a few solid over hand at the cut end of the rope to prevent any potentially fatal slippage of the sheath. Refer to the picture to help visualize how a few of these cutting techniques might be done. Cutting the rope is never a recommended solution to a stuck rope as it can leave your line too short for the following rappels. Certain techniques, skill sets and training are required to correctly pull, extract and/or resolve retrieving a stuck rope.

04-03: Clipping into Bight 03 – Quick Anchor Fix

Tailing up a rope as mentioned in our previous tech tip posts in this series has its advantages. Tailing up a rope also and more conveniently makes for an immediate and very simple solution for ascending/descending a fixed line– because every now and then, fixing a rope either becomes a necessary or preferred system when a team chooses to either employ various technical devices to assist in ascending a fixed line, speed up the overall progress as a team, and/or to aid or assist or use for potential self-rescue purposes…and also not to mention positioning oneself to take some great photos, too.

Tailing up a rope as mentioned in our previous tech tip posts in this series has its advantages. Tailing up a rope also and more conveniently makes for an immediate and very simple solution for ascending/descending a fixed line– because every now and then, fixing a rope either becomes a necessary or preferred system when a team chooses to either employ various technical devices to assist in ascending a fixed line, speed up the overall progress as a team, and/or to aid or assist or use for potential self-rescue purposes…and also not to mention positioning oneself to take some great photos, too.

1. ANCHOR A: Assuming the tail rope has been clipped into a well dressed Figure 8 on a bight, the tail rope can instantaneously be clipped or fixed directly into the master point of the anchor.

2. ANCHOR B: No pre-constructed anchor? Tail up a single Fig. 8 on bight, clip into one anchor point, retrieve roughly 2+ meters of rope and clip that into second anchor point with a clove hitch or overhand knot, equalize both points in the proper direction or line of fall with a single or double overhand and/or Fig. 8 knot on a bight. Clip two opposed locking carabiners into the master point followed by fixing the climbing end of the rope into the opposed carabiners. This may become particularly useful when the anchor becomes overcrowded and a secondary anchor is needed.

3. ANCHOR C: Tailing up a Bunny Ear Fig. 8(a.k.a. Double Fig. 8) with elongated “ears” allows for quick and easy equalization off each hanger followed by a standard stopper knot on the working end of the line. OR if you need something more redundant than a 2-point anchor and/or and/or have the patience/time, there is also the possibility to alter your Bunny Ears Fig.8 knot into an equalized Triple Point Fig. 8 Knot.

NOTE: For the less than sure-handed, always be sure to protect the tail rope a few meters from the end of the rope to the anchor or harness with a Clove Hitch or knot on a bight before unclipping the tail rope from haul/belay loop to prevent the tail rope from falling out of reach down the mountainside.

04-02: Clipping into Bight 02 – Tangles, Terrain & Tailing

The first and most obvious reasons to clip into a Fig. 8 on Bight is typically to by-pass the hassles of untying and re-tying the Threaded Fig. 8 knot back into the tie-in points of the harness over and over again. A lot of extra time can be saved on the time spent tying-in to the harness, re-threading incomplete knots after double-checks and the constant rotation of climbers on and off top-rope climbs in a single pitch top-roping scenario. Clipping in via carabiner can be extremely efficient.

The first and most obvious reasons to clip into a Fig. 8 on Bight is typically to by-pass the hassles of untying and re-tying the Threaded Fig. 8 knot back into the tie-in points of the harness over and over again. A lot of extra time can be saved on the time spent tying-in to the harness, re-threading incomplete knots after double-checks and the constant rotation of climbers on and off top-rope climbs in a single pitch top-roping scenario. Clipping in via carabiner can be extremely efficient.

And although it may seem odd to see teams tying in on multi-pitch climbs this same way, it is definitely no mistake that they have chosen to do so because applying clipping into a Fig. 8 on a bight can also save a team multi-pitching a lot of time and fewer hassles that might otherwise happen with a less proficient climbing team when it comes to rope management, team efficiency and safety With this in mind, keeping an auto-locking anti-rotational HMS carabiner handy can be a nice perk.

1. TANGLE: There are a few general rules that help prevent the common and often persistent problem of “tangle-age” when clipping oneself into a belay station anchor during a multi-pitch climb; however, sometimes even the best applications can fault one’s stack into a tangled nest of frustration and this is where simply unclipping the bight(secondary tether point fixed to anchor) can make untangling a rope much easier and quicker…especially with a large team where overlap of ropes and tethers are more likely to become an issue).

2. TERRAIN: Another case when clipping in on a bight is advantageous is where the terrain and/or grade change significantly and require an immediate change-up in climber sequence. An example of this might be where a climber is required to re-position themselves in the sequence where their specific skill sets and/or strengths can be utilized and applied to benefit the team’s overall safety and performance through a given section. Another case where clipping in on a bight is advantageous might be where the the length of the climbing pitches are continually varying where temporarily clipping in on a bight to shorten(coil) and/or then un-clipping to re-lengthen(uncoil) the climbing rope becomes necessary to help manage a team’s overall tempo and efficiency.

3. TAILING: Tailing ropes up with a carabiner on the bight also saves time when it comes to un/tying ropes along situations that require re-sequencing in the climbers. Plus, clipping bights into the harness loop helps to save space at the harness tie-in loops(A. tying 2 tail ropes into the harness tie-in loops overcrowds harness tie-in points where the climbing rope and tether are already tied in there. B. clipping tail ropes into harness haul loop works fine; however, makes clipping the tail rope(s) into pro along the pitch more difficult where clipping the tail rope(s) into pro is necessary). It’s best to just clip bights into belay loop using an HMS which allows the gate to open more freely and has more space for clipping in more than one tail rope.

NOTE: Always keep yourself attached to the anchor with at least one or more tether points while un/clipping in and out of Fig. 8 bights. Also, to prevent loss of a rope during climb, protect your ropes on anchors or harness points while un/clipping them in/out with a simple overhand, clove hitch and any other secure knot. On constantly varying terrain, at the very least, always be sure to clip carabiner into bight and belay loop together on the climbing end of the rope to prevent strangulation from the coiled shoulder loops. With all of the above in mind, having an anti-rotational HMS auto-locking carabiner handy is a bonus!

04-01: Clipping In 01 – Clipping in to Climb

Tying in to the harness before climbing is a given; however, there are times when clipping into the harness via Figure 8 on bight with a carabiner has its advantages. In this series, we are going to explore how to clip in with the Figure 8 on a bight correctly along with when and where using it can be advantageous.

Tying in to the harness before climbing is a given; however, there are times when clipping into the harness via Figure 8 on bight with a carabiner has its advantages. In this series, we are going to explore how to clip in with the Figure 8 on a bight correctly along with when and where using it can be advantageous.

For many, but not all, clipping into the harness may not feel as secure as tying directly into their harness because it is just one more link in the system to worry about possibly going wrong. However, and more importantly, tying in with a single screw-gate HMS carabiner is not the ideal choice or way to clip into because more often than not the movement and/or belay of the rope can jiggle the carabiner(s) around freely causing the carabiner(s) rotate into a cross-loaded position and additionally loosen the screw gate into an unlocked position. Not only are there a number of ways to either prevent or remedy this from happening, but there are also techniques used to safely clip in with a single locking screw-gate HMS carabiner as well BECAUSE ONE THING IS FOR SURE, we all want to hone in more on our actual climbing without the fear and/or worries of whether or not we have clipped in to climb safely!

1) The first and easiest way to fool-proof any rotation and/or repositioning of the carabiner is to simply go out and buy one of the many specially designed HMS auto-locking carabiners(.e.g. Elderrid HMS Strike Slider Safelock, Gridlock, BD Metolious Gatekeeper, DMM Master Belay2, etc.) Not only are they designed to address and prevent the aforementioned problems from arising, they are very easy to just clip in and climb on with.

2) Clipping in with two opposed HMS carabiners is nearly the equivalent to clipping in with a single anti-rotational auto-locking HMS, but whereas the anti-rotational auto-locking HMS simple locks itself shut and is fixed to the belay loop, the opposed locking carabiners are not fixed to the belay loop(e.g. preventing rotation) nor prevent vibrations in the rope plus gravity from unscrewing the gates, the opposed carabiners do in fact highly reduce the chance of tie-in system failure to nearly nil by preventing both carabiners gates from opening at the same time and or from the same side.

3) For the singular manually locking HMS carabiner, it is wisest to cinch or minimize the Fig. 8 bight loop down to a very tight and slight diameter– so much that the carabiner becomes unable to rotate or slide around easily into a X-loaded position and/or screwgate up position without deliberately trying to do so. The easiest way to accomplish this is by first making the Fig. 8 on bight and pulling the strands of the bight tightly and around to the free-ends of the knot until the bight is just barely large enough to clip the HMS in so that when/if a fall is taken, the bight doesn’t loosen/enlarge so much that the HMS can later slip around and rotate freely. Be sure to shut all gaps in the knot to prevent any loosening and/or enlarging of the bight loop and maintain the orientation of the carabiner in the screw-gate down so you don’t screw up position of the belay loop! (This technique can also be used to prevent the rotation of two opposed locking carabiners and/or a single auto-locking carabiner without an anti-rotational feature)

4) With a slightly ridiculous twist, but creative stretch of the imagination, one can clip a single locking carabiner into their belay loop, then clip a heavy grade rubberband into that same carabiner, give the rubber band a few X pattern crossovers over and around the belay loop and finish by clipping the remainder slack of the rubberband into the carabiner to immobilize any movement or rotation of the carabiner. This can also be combined with the above tip(3), also. Again, this technique can also be used to prevent the rotation of two opposed locking carabiners and/or a single auto-locking carabiner without an anti-rotational feature.

5) Though counter-intuitive, clipping into both harness tie-in loops would seem redundant or safer; however, the bulkiness of the tie-in points causes the carabiners to position themselves into a cross-loading position(e.g. esp. belaying and rappelling) more easily. The bulkiness also braces the HMS into position– making it less likely to rotate, but consequently enabling an unlocked screwgate to more easily unlatch when bumped because it is bolstered by the bulkiness of the tie-in loops. And, although removing the HMS from the two tie-in loops more difficult, this is not the case for the knot that is clipped into the HMS that has beeen clipped into the tie-loops!

NOTE: Clipping in with the above methods are meant for seconding only– not leading! Be sure to always keep screwgate aimed in down position, so you don’t screw up(doesn’t apply to the automatic self-locking anti-rotational HMS carabiners).

03-03: Knots 03 – Threaded Figure 8 Knot

Threaded Fig. 8 is the most popular choice for experienced and beginner climbers alike. For beginners, this knot not only appears heftier and more solid which encourages more confidence in it, it also has multiple contact points of friction– cinching down on itself when weighted or shocked; and is also easy to self/double-check once properly learned how. For some experienced climbers, the Bowline is the knot of choice because it is quicker to tie in with and much easier to loosen and untie from compared to a shocked and tightly cinched down Threaded Fig. 8 knot.

Threaded Fig. 8 is the most popular choice for experienced and beginner climbers alike. For beginners, this knot not only appears heftier and more solid which encourages more confidence in it, it also has multiple contact points of friction– cinching down on itself when weighted or shocked; and is also easy to self/double-check once properly learned how. For some experienced climbers, the Bowline is the knot of choice because it is quicker to tie in with and much easier to loosen and untie from compared to a shocked and tightly cinched down Threaded Fig. 8 knot.

For the experienced climbers who prefer to stay with the Threaded Fig. 8 because it feels and looks safer, the hassles of dressing the Fig. 8 knot perfectly every time plus the struggles of loosening a tightly cinched knot after several lead or top-rope falls can often be a discouraging factor to bother tying-in with it rather than with the Bowline; however, tying-in with the Threaded Fig. 8 knot does not have to be quite so frustrating with a few of our very simple and very helpful pointers.

1) There are plenty of climbers who have climbed for years who either don’t how they dressed the Threaded Figure 8 Knot perfectly or end up wasting time over-manipulating it to dress it perfectly. Getting the the knot dressed right on purpose the first time, every time is not difficult to do, and once understood, takes absolutely no time at all. After threading the strand end of the starting framework for the Threaded Fig. 8 Knot through the harness’ two tie-in loops, follow the tail-end back along the framework all the way to the end while maintaining that the threading end always stays adjacent or along the same side of the rope as it is snakes and wraps its way back to the rope’s end. By carefully keeping adjacent or continually on the same side, the knot will appear flat and uniform with two prominent pairs of bends in the knot(harness-facing end pair and rope-facing end pair). Take outer bend of one of the bend pairs(e.g. harness-facing bend pair) and roll it over its adjacent inside bight and do the same for the opposite pair of bends(e.g. rope-facing bend pair). Noticeably, rolling the outer bend over its adjacent inside bend is the natural and only direction to roll the outer bend. From here, tighten each of the four of the knot’s strands separately, individually and oppositely(like one might rotate the tightening sequence of the nuts while changing the tires on a car) in order to close all of the gaps of in the knot. Be certain your knot has sufficient tail or roughly 5 inches plus.

2) Always take the time to either double-check your partners’ or do a proper self-check of the Threaded Figure 8 Knot before climbing on. A proper double-check includes a belay loop-sized bight threaded through both tie-in loops, having the knot roughly a fist-lengths distance from the tie-in loops, roughly 5 inches of tail, a uniform and symmetrically dressed knot with all gaps in the knot closed. ALWAYS count off 5 pairs from the harness end to the to finished end of the Threaded Fig. 8 Knot– if you cannot count 5 pairs off, re-check the knot and/or re-thread it. Though not necessary, finishing stopper knot, Yosemite Finish and/or the Fig.8 Follow-through are optional. NEVER tie the Threaded Fig. 8 Knot into the belay loop, but always into both harness tie-in loops.

3) The knot cinches down hard on itself while taking the shock of lead and top-rope falls which can make loosening the knot in order to untie the Threaded Fig. 8 Knot very difficult and sometimes nearly impossible at times to undo. A simple trick to loosen the knot is by rolling the outer bends(e.g. harness-facing bends away from the knot while simultaneously pushing and wiggling the pair of strand-ends of the knot back into the knot). Repeat this on the other end of the knot and repeat if necessary. This technique also works very well with the Yosemite Finish, Figure 8 Follow-through, and a regular Figure 8 on a bight, too. NEVER whack the knot into a hard surface or gnaw or dig at it with teeth or pointed object to free it up like some climbing savages have actually been witnessed to do.

4) The loop of the knot should roughly be about the same diameter as the belay loop and the knot shouldn’t sit more than a fists length off your harness(unless the climber enjoys being smacked in the face by the knot during a “whippy” belay); likewise, if the loop of the knot was made too large and far away off the harness tie-in loops, rather than completely untying and starting over from scratch, it’s easiest to loosen the knot a bit, grab the doubled rope strands and push, slide and/or work them and the knot closer to the harness. And finally, close the gaps back up by re-tightening the knot. If this leaves excess tail, just do multiple wraps on the finishing stopper knot.

NOTE: No matter what, ALWAYS take the extra time to do a proper self or double-check on you or your partner’s tie-in knot. Some very basic self-checks for the Threaded Figure 8 Knot might be being certain that the rope has been threaded through both tie-in loops on the harness(i.e. not into the belay loop or on into a singular tie-in loop), being able to count five rope-strand pairs off, being sure the strand-end of the rope comes back on itself to finish off the knot along with at least roughly five inches of tail, each of the four strands has been cinched enough to shut any gaps in the knot, and that the loop of the knot is roughly the same circumference as the belay loop.

We strongly encourage the use of the Threaded Figure 8 Knot over the Bowline Knot to tie in with before climbing for beginners and those who are not familiar with the Bowline Knot. Although the Bowline is very simple once mastered, it also can become very confusing to tie in with correctly and safely; and is also difficult to double-check for those unfamiliar with its nature.

03-02: Knots 02 – Nots of the Knots

The NOTS for knots are many and it is more often than not that some of the most basic of the NOTS predictably, but unexpectedly lead to accidents. Stressing the importance of doing proper double-checks on knots is without question the prudent, rudimentary and obviously appropriate thing to do before dangling our lives out into the open void off a cliff face; however, the scary irony is that despite knowing better– complacency can have its way with even some of the most experienced climbers, and can result in an accident that ends in injury and sometimes in fatal tragedy.

The NOTS for knots are many and it is more often than not that some of the most basic of the NOTS predictably, but unexpectedly lead to accidents. Stressing the importance of doing proper double-checks on knots is without question the prudent, rudimentary and obviously appropriate thing to do before dangling our lives out into the open void off a cliff face; however, the scary irony is that despite knowing better– complacency can have its way with even some of the most experienced climbers, and can result in an accident that ends in injury and sometimes in fatal tragedy.

So doing double-checks on knots is an emphasized given. A few of the most important NOT of the knots are done before and while tying in before the climb, while other NOTS have to do with connecting two rap lines together and/or to do with making the mistake of assuming stopper knots at the end of a rap line will prevent one from sliding straight off the end of the line…here are some explanations where some of the NOTS actually count for more than the knots themselves!

1) DO NOT forget to always do a proper self-check of the knot you are using to tie into your harness or at the very least have someone who does know the knot well do the self-check for you. There are a lot of ways to tie into a harness and methods for self-checking various knots, so be sure you not just understand the nature of the knot inside and out, but mainly that you also know how to do a proper self-check for that knot and also have your partner(s) double-check your knot before climbing on.

2) DO NOT blabber away and joke around so much that you lose sight of what you are doing while tying in because NO ONE will be joking or laughing after the knot fails or undoes itself during a lower, take or a fall. Unfinished or unchecked knots due to this kind of complacency with even seasoned climbers is one of the most common mistakes that lead up to knot failure accidents, serious injury and sometimes even death. PLEASE do yourself and your team a favor and take the extra silent moments to simply focus on specifically tying in and doing proper redundancy and buddy or self-checks.

3) DO NOT connect two ropes of the same color together for your rappel without doing a proper, accurate and very thorough double-check of the connecting knot and its back up knots. Unfinished connecting knots(e.g. overhand knot) of the same colored ropes have been known to be visually deceiving or mistaken to look as if the connecting knot(s) has been properly dressed and finished, and consequently result in knot failure while the last makes their rappel. Different colored ropes visually aid and help to more clearly discern that both ropes have been properly connected together.

4) DO NOT assume stopper knots for a double or single line abseil will prevent one from rapping off the end of the line while using Super8 device, Munter Hitch and/or similar open ended rappel devices or rapping methods on lead rappel. Stopper knots are specifically for the stitch-plate or similarly designed ATC devices which do not allow for the stopper knot to feed through the rappelling devices rappel slots. The Super8 and Munter Hitch via HMS carabiners, unfortunately by design and nature, unlike the aforementioned devices, easily allow for the stopper knots’ to slide or run through. (4a) For double-line rappels, it is best to connect the tail ends of the rap lines together with a solidly dressed knot(Figure 8 with stopper knots with sufficient amount of tail recommended) and clip a secondary locking carabiner off the tether(e.g. multi-chain) into only one of the rap lines and within arm’s length reach; hence, the secondary carabiner maintains redundancy inside the enlarged, but enclosed loop of the two rappel lines(the carabiner also helps to mark which line to pull for those longer rappels where two ropes is required). An extended auto-block off the tether or harness(e.g. multi-chain) with plenty of clearance from the rappel device or HMS is a bonus– giving the abseiler more control, and would also act as an auto-block as it jams itself up on the connected stopper knot and setting the auto-block(e.g. prusik) into the locked position. (4b) For single-line rappels, it is safest to tie the tail end of the rope into one’s harness(e.g. like one might do so for a climb) and use an extended auto-block off(e.g. off multi-chain) with plenty of clearance from the rappel device or HMS for increased security and control. The same could also be done for the double-line rappel, but might increase the difficulty of managing the ropes on lead rappel.

NOTE: Know how to do your double-checks on the knots you intend to use. Always make certain that not only are your knots dressed properly, but also that the knots have been cinched sufficiently and tight enough to close any of the gaps or spaces in the knot. Also, be sure to leave a sufficient amount of tail at the end of the knots along with additional back-up knots. Auto-blocks must maintain enough clearance from and/or not interfere with the Super8 or HMS when in the locked position to prevent the device or HMS from mistakenly releasing the auto-block from the locked position– this is especially more prone to happen when the the auto-block has been fixed off a leg loop upon bending or lifting one’s leg up while rappelling.

In these discussions, the positive role of an ascending carbon or cheap cialis slovak-republic.org gasoline tax in weaning America off petroleum is not often mentioned. If the sperm fails to attain a chance to mingle with the eggs present within the fallopian tube, then it travels out from the rat race. cialis buy uk This company is a reputed source of cheap cialis uk information about drugstores functioning online. The longer cGMP persists, the more prolonged the engorgement of the discount viagra sales penis with blood.

03-01: Knots 01 – Knot Fun

There are times after tying in when knots mysteriously appear either between scrambles, between belay stations and even shortly after flaking the rope somehow. The knot has to be undone to allow the rope to run freely through carabiners; and if the knot is not undone, the knot, consequently, will cause a number of problematic scenarios and can potentially immobilize a team’s progress until the knot is resolved. Imagine being unable to feed the rope through the belay device while lead belaying, being unable to advance due to a knot in the tail rope getting caught on a carabiner several meters below, or finding your top rope has become overly slack due to a knot not just caught in a carabiner a few meters, but also as a consequence obstructs your belayer from tightening the belay. All of the mentioned scenarios can be resolved by an experienced climber with the appropriate skills sets and techniques. Regardless of the scenario, a knot along the rope can become a lot of extra work, cut into a team’s time and possibly become nightmare for those who lack experience and the technical know-how, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

There are times after tying in when knots mysteriously appear either between scrambles, between belay stations and even shortly after flaking the rope somehow. The knot has to be undone to allow the rope to run freely through carabiners; and if the knot is not undone, the knot, consequently, will cause a number of problematic scenarios and can potentially immobilize a team’s progress until the knot is resolved. Imagine being unable to feed the rope through the belay device while lead belaying, being unable to advance due to a knot in the tail rope getting caught on a carabiner several meters below, or finding your top rope has become overly slack due to a knot not just caught in a carabiner a few meters, but also as a consequence obstructs your belayer from tightening the belay. All of the mentioned scenarios can be resolved by an experienced climber with the appropriate skills sets and techniques. Regardless of the scenario, a knot along the rope can become a lot of extra work, cut into a team’s time and possibly become nightmare for those who lack experience and the technical know-how, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

The most important thing is spotting the knot with enough time to spare to undo the knot before it has a chance to run itself on a carabiner and obstruct further advancement of the rope. Rather than waiting for the knot to come up on you at the last minute while belaying or feeding rope out, identifying the knot beforehand is best done by re-flaking the rope in advance at a wide enough terrace or platform. Identifying the knot in advance while at a hanging belay is best done by flicking 3~5 meters of loop strands off from the belay brake strand end pile of the rope out down the wall(but also being sure these loop strands are clear from being caught in or on the terrain below(e.g. roots, cracks, horns, etc.).

Here are a few pointers to quickly and easily undo or resolve the ever-so burdensome knot amidst any one of the aforementioned scenarios.

1) Whether on the ground or at a belay station, when you’re tied in and ready to go, but find a knot in the middle of the rope, the quickest solution is to slide or work the knot down the rope to your harness or tie-in knot. The same can go for while lead belaying your partner and finding a knot on the brakehand strand end of the rope– simply slide the knot away from the belay device while maintaining a hand on the brake(this can be a lot of work alone, but not impossible while belaying. So, if possible have a teammate help out instead).

2) If you are on safe level ground at the start or between pitches that doesn’t demand you be tied in and find a knot in your rope, the above also applies. But, even better yet, just enlarge the knot enough and step through it like a giant loop. If you are tied into an anchor, you can do the same thing by enlarging the loop and pulling it over and around you; however, by doing so, this would create a knot in the rope you might be tailing up, so it’s best to untie from and tie back into your tail rope before doing so. Also, if the knot is so far up the rope that sliding it down and then stepping through it seems like a lot of time and work, just grab your stack from your end of the knot and step through the knot (or loop it over and around your head) with your stack.

3) A common practice by large Korean teams is for the top-ropers to tie-in with locking carabiner via a Figure 8 on a bight. Tying in with this approach has it’s advantages and disadvantages. One of the major advantages is being able to immediately remove or unclip the rope end from the climber’s harness which frees the rope up as a whole and allows one to more quickly and easily resolve the rope problem; however, it’s disadvantages are that untying or unclipping in this manner leaves the small chance of the belayer from above pulling the rope up and out of reach(always maintain control or possession of the rope!). And, by tying in via locking carabiner plus figure 8 on bight leaves the potential for the carabiner to rotate or disorient itself in the knot itself or in the belay loop(more on this later).

4) Good team and rope management at each station is the key to preventing knots from occurring in the middle of a climb. When tying into your belay station, tie in under ropes– this will keep the ropes on top and “floating” above all of the tied-in tethers. Tie into the anchor in order and in sequence– not doing so causes rope stacks to become intertwined and tangled with each other which can lead to a very big rat’s nest of messy, tangled rope. Be mindful of how the rope is being stacked while belaying others up from below(smaller to longer loops to prevent loops catching in loops which cause tangles) and flipping stacks over onto the following climber’s tether just before climbing on.

NOTE: Never completely untie from your anchor while resolving a knot. Instead, resolve knot problem as mentioned above, but back yourself with a secondary tether to the anchor before maintain redundancy while untangling your tether from the rope!

02-03: Climbing Signals 03

To climb or not to climb, that is the question on a multi-pitch climb while waiting for that signal to climb on. Multi-pitch climbs are also more committed and take much more time. Being on a big wall or ridgeline not only commits a team from making a quick and easy retreat, but also increases the amount of time that a team spends on their route. And as a consequence, multi-pitch climbs increase the chances of becoming exposed to deteriorating weather and/or nightfall. There are a lot of factors that can contribute to a team’s overall efficiency and time out on the climb– climbing signals is definitely one of them, but doesn’t have to be.

To climb or not to climb, that is the question on a multi-pitch climb while waiting for that signal to climb on. Multi-pitch climbs are also more committed and take much more time. Being on a big wall or ridgeline not only commits a team from making a quick and easy retreat, but also increases the amount of time that a team spends on their route. And as a consequence, multi-pitch climbs increase the chances of becoming exposed to deteriorating weather and/or nightfall. There are a lot of factors that can contribute to a team’s overall efficiency and time out on the climb– climbing signals is definitely one of them, but doesn’t have to be.

Bad communication and poor signaling systems not only increase a team’s exposure to the changing elements, but also ineffectively cause longer waits between belays that could have better been spent advancing instead. In some scenarios, the second never hears the belayer’s signal or vice-versa and both stand there unknowingly waiting on the other to move or call out killing up to half an hour in some cases! Likewise, consider this that if it takes an average of only an additional 5 minutes per climber at each station to start climbing for a team of three climbers up eight pitches due to mediocre communication– that would end up adding 2.5 extra hours to the climb!

Given the above, rope signals are definitely the preferred choice to signal with on multi-pitch climbs because as long as the rope signals are being effectively employed, they will inevitably contribute to a team’s overall efficiency. Here are a few scenarios and effective techniques to consider:

1) You have somehow allowed yourself on a team that hasn’t gone over how they are going to signal in advance, don’t understand their language or poor signalling system result in bad miscommunication. Some cues to look for as a second to ensure you are on belay before unclipping your tether from the anchor might be watching for rhythmic and steady tugs on the rope while slack is being collected between you and your belayer because this is not definitely, but most usually a positive indication that the belay has been pre-loaded. Continued yanking on your end of the rope is also, but again not definitely, a very good sign that you are on belay. Additionally, taking a few steps forward or up as a test(while still tied in to anchor, of course) to see if the rope gets pulled up and remains relatively tight, is also a good indication that the belay is on, too. If there are still serious doubts that you are on belay, and you have a third at your anchor and at your disposal, have the third give you a belay(on your tail rope(tail rope tied properly tied into harness tie-in loops) until you are confident that you are on belay(from above)…though, at best, the third’s belay works no better than a lead belay if you’re not on belay from above and is far from ideal, some sort of back up is always better than none!…DEFINITELY BEST to climb with a team who has their signals straight to avoid this scenario period!

2) Agree on a rope tugging signaling system amongst your partners which might be something as simple as three tugs followed by continued tension on the rope meaning you are on belay. This is up to the climbers of the team where the bottom line is that the rope signals are understood on both ends of the rope. A good resource to refer to practice such a system might be the Marhold Tug(Adaptive Climbing Manual, Paradox Sports, 2015) which combines both systematic verbalized calls with tugs. Never confuse the tugs of loading the belay device for being on belay! Regardless of the chosen rope signalling system, the most important thing is the system is has been practiced and is clearly understood on both ends of the rope!

3) SAN Signals were developed over the years as a means to teach our climbing school students and clients how to know when it is safe to climb. It works entirely on physical rope signals alone and is simple and to the point, but requires that things are understood on both the belay and climbing ends of the rope. In a nutshell, once the belayer has tied in safely, they reel in the slack up until they feel their second, and immediately let enough slack back down to make it obvious to their second that they are not on belay. S/he proceeds to load the belay, do their double-checks and pull up the remaining slack in tightly and with forceful deliberate tugs to ensure the second understands they are on in fact on belay. The forceful tension is maintained on the second until they have climbed at least five plus meters to prevent miscommunication– this method is also to instill confidence in the second that the belay is on and to prevent any busted ankles(especially from a terrace or the ground up). On a 30+ meter pitch, it is important to emphasize the tension with deliberate intention to ensure that the second can feel they are on belay due to the softening of the pull due to the rope stretch.

NOTE: Direct rope signals to be the second’s harness can be obstructed or not appropriately felt when climbing rope-end is tied into the anchor as a tether or back up for the tether. It is the responsibility of the team to keep the rope clear from impending friction, jamming or pinching points that might interfere with the clean and free movement and signaling of through the rope. Never confuse the tugs of loading the belay device for being on belay!

02-02: Climbing Signals 02

While waiting to climb on, verbal signals work well on multi-pitch climbs in ideal conditions; however, verbal signals more often than not can fail us on multi-pitch climbs where physical rope signals may not during the ever-constant changing nature of multi-pitch climbs. There are some very important and often overlooked fundamental reasons as to why not to call out signals during a multi-pitch climb by both experienced and beginner climbers alike. Here are some reliable factors to consider before venturing out without a back up set of rope signals on your next multi-pitch climb:

While waiting to climb on, verbal signals work well on multi-pitch climbs in ideal conditions; however, verbal signals more often than not can fail us on multi-pitch climbs where physical rope signals may not during the ever-constant changing nature of multi-pitch climbs. There are some very important and often overlooked fundamental reasons as to why not to call out signals during a multi-pitch climb by both experienced and beginner climbers alike. Here are some reliable factors to consider before venturing out without a back up set of rope signals on your next multi-pitch climb:

1) On multi-pitch climbs, more often than not, the climber ahead who will be giving the next climber their belay ends up out of sight which makes the next climber even more so reliant on having to be able to hear the belayer’s verbal signal clearly and accurately– which is not always guaranteed. Rain, fog, snow and also the dark can also impair your vision, too.

2) Although this is less likely to happen for the English speaking climbers in Korea, but more specifically, when there are other climbing parties nearby, voicing signals could easily get confused with another team’s signals which as one can imagine, could result in a lot of potential problems.

3) Multi-pitch climbs are longer, thus increasing the chance for the weather to change. Anything from the pitter-patter of the rain to the muffling effects of the fog or snow can plug up one’s hearing. Also, the rustling of a light breeze to the howling gusts of the wind can also play tricks on our ears!

4) There are very few multi pitch climbs that do not do some zigging, zagging or sticking out of some sort. Bends, bulges, overhangs and other oddly shaped formations in the terrain(even thick bushes and trees, too) or along the route make for excellent sound barriers which can make it very difficult to voice signals back and forth.

NOTE: When verbal signals break down, bad communication and/or poor signaling systems may follow suit; which in turn, can decrease a team’s overall time efficiency throughout the course of the day. Bad communication and poor signalling systems not only cause a lot of frustration and bickering, but ineffectively causes longer waits between belays. Longer waits between belays equals more time wasted that could have otherwise been spent more effectively advancing instead. For example, if only an additional 5 minutes were wasted per each belay stance for each climber for a team of four on an eight pitch climb(that’s only 3 belays per pitch) due to poor signalling, 120 minutes or 2 hours have just been wasted. This might be the difference between being caught in crappy weather or in the dark and being down off the mountain enjoying a beer! Be sure you and your partners have a reliable set of rope signals…more on this later.

02-01: Climbing Signals 01

Whether climbing at the gym, out at the sport crag or on a multi-pitch climb, regardless of what a team’s signals are and how a team decides to relay or exercise those signals– it is should go without fail that the signals the team chooses to use be clearly addressed, understood, and agreed upon(and perhaps also practiced in some cases) beforehand by all members of the team; otherwise and more often than not, it will be more than one’s misunderstood signals that will be effectively communicated!

Whether climbing at the gym, out at the sport crag or on a multi-pitch climb, regardless of what a team’s signals are and how a team decides to relay or exercise those signals– it is should go without fail that the signals the team chooses to use be clearly addressed, understood, and agreed upon(and perhaps also practiced in some cases) beforehand by all members of the team; otherwise and more often than not, it will be more than one’s misunderstood signals that will be effectively communicated!

Keeping signals simple, curt and to a minimum are key to avoiding confusion and/or unnecessary misunderstandings between climber and belayer. Standard verbal signals like, “ON BELAY, CLIMBING, CLIMB ON, TAKE(UP-ROPE), SLACK, DOWN(LOWER), OFF-BELAY” generally work fine as commands during single pitch climbing scenarios because not only are both climber and belayer typically within close sight of each other, but also well within clear earshot as well. For now, the following is meant to only to help make one verbalize their signals more effectively when in use regardless of where or how they are might be.

Verbal Signals:

1) Direct your voice appropriately in the direction of your climber. Shouting your signals at your anchor, casually off to the side or even out into the open directly behind you into empty space may not deliver your signal effectively enough to your partner. Aim your shout at your partner.

2) When in doubt as to whether or not your partner heard the signal, simply repeat by cupping your hands(keeping brake line in hand or backed up) around your mouth to help amplify your shout. Whether it is actually more effective might be in question, but it can’t be any worse without!

3) Take inventory of your surrounding terrain and the terrain that lead up to your anchor. Especially in the case where there is a large bulge which also acts as an effective sound barrier on the last pitch between you and your partner, rock walls are great at reflecting sound, so try aiming your voice instead down and at an opposing wall to help your signal resonate down, off and around the obstructing bulge and to your partner.

4) If you cannot get into a good enough position to direct your voice effectively, extend your anchor or yourself to a position where you can.

5) Though not recommended, appointing a number of syllables for different signals can also help the listener distinguish the proper signal if the signal becomes muffled in the distance without getting confused by similar sounding or same syllable number signals. This system to voice signals based on syllable count is effective, but only as long as the climbers can hear the signal and are also paying close attention to the syllable count. It would be recommended to rehearse the signals.

6) Though not recommended, communication devices also work well; however, it only takes one of the two devices to fail to make both obsolete. A few problems that might arise are as follows: batteries die due to a number of reasons(fresh batteries at start plus spares are a bonus), device malfunctions(lemon or banged up), unbeknownst button-pushing causing channel changes, reception and clarity becomes distorted making signals difficult to understand, forgetting to turn the radio on every X minutes in order to conserve batteries, etc. Always be sure to have a back-up signalling method in place under the unfortunate circumstance that a radio fails.

NOTE: Physical signal/checks along with verbal signals build not only build more confidence and trust between climber and belayer. Verbal signals alone are not recommended on multi-pitch climbs due to a multitude of varying circumstances…stay tuned for more on this.

01-03: Rope Care 03

There are a lot of obvious and not quite so obvious reasons not to step on ropes aside from plain just irritating the heck out of the rope’s owner. This tends to more commonly happen among the less experienced climbers and ordinary onlookers passing(especially here in Korea) by who do not understand the value of ropes. While there are some circumstances that doing so is appropriate; for example, like while loading up an anchor belay in order to prevent one’s stack from unraveling on a multi-pitch climb or while loading up your rappel line to simply making the heavy rope(s) lighter and easier to load one’s device, there are also a few not so new and new reasons as to why not to:

There are a lot of obvious and not quite so obvious reasons not to step on ropes aside from plain just irritating the heck out of the rope’s owner. This tends to more commonly happen among the less experienced climbers and ordinary onlookers passing(especially here in Korea) by who do not understand the value of ropes. While there are some circumstances that doing so is appropriate; for example, like while loading up an anchor belay in order to prevent one’s stack from unraveling on a multi-pitch climb or while loading up your rappel line to simply making the heavy rope(s) lighter and easier to load one’s device, there are also a few not so new and new reasons as to why not to:

1) Stepping on the rope damages the rope by directly fraying the sheath. Help prevent this from happening by piling the rope out of the away from the belayer or other climbers may actively be need to step around or through. As absurd as this may sound, “blockading” the rope with your backpack or something may also make walking through your pile an obstacle not worth the effort.

2) Stepping on the rope grounds dirt and other rough particles into the rope. Help prevent this from happening by piling rope as in above Example 1; plus, piling the rope high and off to side or also on cleaner bare rock surfaces(i.e. out and away from dirt) and/or also on a rope tarp, in a rope bucket, etc.

3) Stepping on the rope can cause one to slip and potentially dangerously lose one’s balance. The rope’s shape is similar to that of a cylinder and by stepping on it, the rope can cause your foot to roll on it like a wheel which could effectively cause one to easily slip and lose one’s balance and possibly much worse! Prevent this by being aware, making those around you aware and managing your rope safely off to the side and out of the way.

NOTE: Pinching or gently stepping on the rope to help load up one’s rappel is pretty common on the rock, but also aside from the obvious reason of not doing so in the winter with sharply pointed crampons, the rope is likely to slide between the slippery cold steel and ice, causing your pile to unravel while prepping an anchor belay or abseil, and of course, allowing the crampons sharp edges to catch on or even fray into the rope, too. Instead, it’s wiser to just pull some slack up and fix the weighted strand somewhere with a clove hitch and/or use a partner to hold the rope for you while loading the heavy rope.

01-02: Rope Care 02

There are a lot of ropes out there with colors both different and similar alike. Choosing a unique color to distinguish your own rope from other teams’ ropes is a very common and obvious thing to do when making your purchase, but at times may still not prevent other teams from mistaking your rope for theirs and taking it down off the mountain or start using it for their own purposes before it’s become too late. This usually occurs when a member of the other team is not familiar with their own team’s ropes, so here are a few extra less obvious reasons to also tape or mark the ends of your rope:

There are a lot of ropes out there with colors both different and similar alike. Choosing a unique color to distinguish your own rope from other teams’ ropes is a very common and obvious thing to do when making your purchase, but at times may still not prevent other teams from mistaking your rope for theirs and taking it down off the mountain or start using it for their own purposes before it’s become too late. This usually occurs when a member of the other team is not familiar with their own team’s ropes, so here are a few extra less obvious reasons to also tape or mark the ends of your rope:

1) Taping the rope’s end witha fat sticker or taping it with multiple colors is a great way for other teams to know your rope is not theirs(especially since the company rope end tabs are generic and more often than not eventually wear and fall off, too).

2) Taping the rope’s end is also more efficient and saves time before tying in for your climb because it helps one immediately spot and find the rope’s end which might otherwise kill time unnecessarily whilst being lost in that vast pile of stacked sameness.

3) Taping the rope’s ends with different colored tape can give a climber more psychological confidence in their rope by cueing the climber as to which end of the rope to tie into or not by marking the frayed end with RED colored tape. Likewise, it signals the climber which end is best to tail up or not for their second on a multi-pitch climb with a 3+ member team.

NOTE: If your rope is overly frayed or damaged on one end from either projecting a cruxy overhang and/or mistakenly splicing into it with your ice pick while seconding(hopefully not both), CUT THE DAMaged end off and make a note of how short the rope has become!

01-01: Rope Care 01

There are lots of ways to clean a rope, but not quite so many ways when you lack a washing machine, tub and/or water– especially out at the crag. Bringing along a few white rags to clean the excess dirt and dust off can be a real bonus out there. Here are a few ways!

There are lots of ways to clean a rope, but not quite so many ways when you lack a washing machine, tub and/or water– especially out at the crag. Bringing along a few white rags to clean the excess dirt and dust off can be a real bonus out there. Here are a few ways!

1) Wrap the rag around the rope near one end of the rope and while grasping the rag/rope with HAND A, pull and run the rope through with HAND B to the opposite end of the rope. More importantly, rotate HAND B as you are pulling the rope through in order to give the rope a more thorough wiping. Repeat via the opposite end back again and again to your satisfaction with the dry rag. After maybe 10 times or to your satisfaction, dampen your rag and repeat a few times back and forth.

2) Since most of us don’t go out to the crag alone, speed the process up by having others hold with more rope wrapped rags and have one person pull rope through. Repeat, etc.

3) If you are alone, just wrap the rope a few times and securely clip a carabiner into the rag and clip it off the ground to slung tree(or maybe even the first hanger of a route, etc.) and pull away.

You just can’t seem to cut it after a long day of climbing and for some reason or another it has come to doing the almost unthinkable– cutting your own rope. This situation doesn’t come up often, and even less so if you are thoughtful, careful and skilled at pulling your rope and/or know how to resolve and retrieve a stuck rope safely. Our solutions on how or what to cut your rope with may not be the prettiest or cleanest methods, but they do the job and get you on your way. Here we go, from best to worst…and of course, the first option and/or any of the following options make the lower listed options obsolete, but fun to entertain the thought. Make it easier on yourself and buy a lightweight knife!

You just can’t seem to cut it after a long day of climbing and for some reason or another it has come to doing the almost unthinkable– cutting your own rope. This situation doesn’t come up often, and even less so if you are thoughtful, careful and skilled at pulling your rope and/or know how to resolve and retrieve a stuck rope safely. Our solutions on how or what to cut your rope with may not be the prettiest or cleanest methods, but they do the job and get you on your way. Here we go, from best to worst…and of course, the first option and/or any of the following options make the lower listed options obsolete, but fun to entertain the thought. Make it easier on yourself and buy a lightweight knife!  Tailing up a rope as mentioned in our previous tech tip posts in this series has its advantages. Tailing up a rope also and more conveniently makes for an immediate and very simple solution for ascending/descending a fixed line– because every now and then, fixing a rope either becomes a necessary or preferred system when a team chooses to either employ various technical devices to assist in ascending a fixed line, speed up the overall progress as a team, and/or to aid or assist or use for potential self-rescue purposes…and also not to mention positioning oneself to take some great photos, too.

Tailing up a rope as mentioned in our previous tech tip posts in this series has its advantages. Tailing up a rope also and more conveniently makes for an immediate and very simple solution for ascending/descending a fixed line– because every now and then, fixing a rope either becomes a necessary or preferred system when a team chooses to either employ various technical devices to assist in ascending a fixed line, speed up the overall progress as a team, and/or to aid or assist or use for potential self-rescue purposes…and also not to mention positioning oneself to take some great photos, too.  The first and most obvious reasons to clip into a Fig. 8 on Bight is typically to by-pass the hassles of untying and re-tying the Threaded Fig. 8 knot back into the tie-in points of the harness over and over again. A lot of extra time can be saved on the time spent tying-in to the harness, re-threading incomplete knots after double-checks and the constant rotation of climbers on and off top-rope climbs in a single pitch top-roping scenario. Clipping in via carabiner can be extremely efficient.

The first and most obvious reasons to clip into a Fig. 8 on Bight is typically to by-pass the hassles of untying and re-tying the Threaded Fig. 8 knot back into the tie-in points of the harness over and over again. A lot of extra time can be saved on the time spent tying-in to the harness, re-threading incomplete knots after double-checks and the constant rotation of climbers on and off top-rope climbs in a single pitch top-roping scenario. Clipping in via carabiner can be extremely efficient.  Tying in to the harness before climbing is a given; however, there are times when clipping into the harness via Figure 8 on bight with a carabiner has its advantages. In this series, we are going to explore how to clip in with the Figure 8 on a bight correctly along with when and where using it can be advantageous.

Tying in to the harness before climbing is a given; however, there are times when clipping into the harness via Figure 8 on bight with a carabiner has its advantages. In this series, we are going to explore how to clip in with the Figure 8 on a bight correctly along with when and where using it can be advantageous. Threaded Fig. 8 is the most popular choice for experienced and beginner climbers alike. For beginners, this knot not only appears heftier and more solid which encourages more confidence in it, it also has multiple contact points of friction– cinching down on itself when weighted or shocked; and is also easy to self/double-check once properly learned how. For some experienced climbers, the Bowline is the knot of choice because it is quicker to tie in with and much easier to loosen and untie from compared to a shocked and tightly cinched down Threaded Fig. 8 knot.

Threaded Fig. 8 is the most popular choice for experienced and beginner climbers alike. For beginners, this knot not only appears heftier and more solid which encourages more confidence in it, it also has multiple contact points of friction– cinching down on itself when weighted or shocked; and is also easy to self/double-check once properly learned how. For some experienced climbers, the Bowline is the knot of choice because it is quicker to tie in with and much easier to loosen and untie from compared to a shocked and tightly cinched down Threaded Fig. 8 knot. The NOTS for knots are many and it is more often than not that some of the most basic of the NOTS predictably, but unexpectedly lead to accidents. Stressing the importance of doing proper double-checks on knots is without question the prudent, rudimentary and obviously appropriate thing to do before dangling our lives out into the open void off a cliff face; however, the scary irony is that despite knowing better– complacency can have its way with even some of the most experienced climbers, and can result in an accident that ends in injury and sometimes in fatal tragedy.

The NOTS for knots are many and it is more often than not that some of the most basic of the NOTS predictably, but unexpectedly lead to accidents. Stressing the importance of doing proper double-checks on knots is without question the prudent, rudimentary and obviously appropriate thing to do before dangling our lives out into the open void off a cliff face; however, the scary irony is that despite knowing better– complacency can have its way with even some of the most experienced climbers, and can result in an accident that ends in injury and sometimes in fatal tragedy. There are times after tying in when knots mysteriously appear either between scrambles, between belay stations and even shortly after flaking the rope somehow. The knot has to be undone to allow the rope to run freely through carabiners; and if the knot is not undone, the knot, consequently, will cause a number of problematic scenarios and can potentially immobilize a team’s progress until the knot is resolved. Imagine being unable to feed the rope through the belay device while lead belaying, being unable to advance due to a knot in the tail rope getting caught on a carabiner several meters below, or finding your top rope has become overly slack due to a knot not just caught in a carabiner a few meters, but also as a consequence obstructs your belayer from tightening the belay. All of the mentioned scenarios can be resolved by an experienced climber with the appropriate skills sets and techniques. Regardless of the scenario, a knot along the rope can become a lot of extra work, cut into a team’s time and possibly become nightmare for those who lack experience and the technical know-how, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

There are times after tying in when knots mysteriously appear either between scrambles, between belay stations and even shortly after flaking the rope somehow. The knot has to be undone to allow the rope to run freely through carabiners; and if the knot is not undone, the knot, consequently, will cause a number of problematic scenarios and can potentially immobilize a team’s progress until the knot is resolved. Imagine being unable to feed the rope through the belay device while lead belaying, being unable to advance due to a knot in the tail rope getting caught on a carabiner several meters below, or finding your top rope has become overly slack due to a knot not just caught in a carabiner a few meters, but also as a consequence obstructs your belayer from tightening the belay. All of the mentioned scenarios can be resolved by an experienced climber with the appropriate skills sets and techniques. Regardless of the scenario, a knot along the rope can become a lot of extra work, cut into a team’s time and possibly become nightmare for those who lack experience and the technical know-how, but it doesn’t have to be this way. To climb or not to climb, that is the question on a multi-pitch climb while waiting for that signal to climb on. Multi-pitch climbs are also more committed and take much more time. Being on a big wall or ridgeline not only commits a team from making a quick and easy retreat, but also increases the amount of time that a team spends on their route. And as a consequence, multi-pitch climbs increase the chances of becoming exposed to deteriorating weather and/or nightfall. There are a lot of factors that can contribute to a team’s overall efficiency and time out on the climb– climbing signals is definitely one of them, but doesn’t have to be.

To climb or not to climb, that is the question on a multi-pitch climb while waiting for that signal to climb on. Multi-pitch climbs are also more committed and take much more time. Being on a big wall or ridgeline not only commits a team from making a quick and easy retreat, but also increases the amount of time that a team spends on their route. And as a consequence, multi-pitch climbs increase the chances of becoming exposed to deteriorating weather and/or nightfall. There are a lot of factors that can contribute to a team’s overall efficiency and time out on the climb– climbing signals is definitely one of them, but doesn’t have to be. While waiting to climb on, verbal signals work well on multi-pitch climbs in ideal conditions; however, verbal signals more often than not can fail us on multi-pitch climbs where physical rope signals may not during the ever-constant changing nature of multi-pitch climbs. There are some very important and often overlooked fundamental reasons as to why not to call out signals during a multi-pitch climb by both experienced and beginner climbers alike. Here are some reliable factors to consider before venturing out without a back up set of rope signals on your next multi-pitch climb:

While waiting to climb on, verbal signals work well on multi-pitch climbs in ideal conditions; however, verbal signals more often than not can fail us on multi-pitch climbs where physical rope signals may not during the ever-constant changing nature of multi-pitch climbs. There are some very important and often overlooked fundamental reasons as to why not to call out signals during a multi-pitch climb by both experienced and beginner climbers alike. Here are some reliable factors to consider before venturing out without a back up set of rope signals on your next multi-pitch climb: Whether climbing at the gym, out at the sport crag or on a multi-pitch climb, regardless of what a team’s signals are and how a team decides to relay or exercise those signals– it is should go without fail that the signals the team chooses to use be clearly addressed, understood, and agreed upon(and perhaps also practiced in some cases) beforehand by all members of the team; otherwise and more often than not, it will be more than one’s misunderstood signals that will be effectively communicated!

Whether climbing at the gym, out at the sport crag or on a multi-pitch climb, regardless of what a team’s signals are and how a team decides to relay or exercise those signals– it is should go without fail that the signals the team chooses to use be clearly addressed, understood, and agreed upon(and perhaps also practiced in some cases) beforehand by all members of the team; otherwise and more often than not, it will be more than one’s misunderstood signals that will be effectively communicated! There are a lot of obvious and not quite so obvious reasons not to step on ropes aside from plain just irritating the heck out of the rope’s owner. This tends to more commonly happen among the less experienced climbers and ordinary onlookers passing(especially here in Korea) by who do not understand the value of ropes. While there are some circumstances that doing so is appropriate; for example, like while loading up an anchor belay in order to prevent one’s stack from unraveling on a multi-pitch climb or while loading up your rappel line to simply making the heavy rope(s) lighter and easier to load one’s device, there are also a few not so new and new reasons as to why not to:

There are a lot of obvious and not quite so obvious reasons not to step on ropes aside from plain just irritating the heck out of the rope’s owner. This tends to more commonly happen among the less experienced climbers and ordinary onlookers passing(especially here in Korea) by who do not understand the value of ropes. While there are some circumstances that doing so is appropriate; for example, like while loading up an anchor belay in order to prevent one’s stack from unraveling on a multi-pitch climb or while loading up your rappel line to simply making the heavy rope(s) lighter and easier to load one’s device, there are also a few not so new and new reasons as to why not to: There are a lot of ropes out there with colors both different and similar alike. Choosing a unique color to distinguish your own rope from other teams’ ropes is a very common and obvious thing to do when making your purchase, but at times may still not prevent other teams from mistaking your rope for theirs and taking it down off the mountain or start using it for their own purposes before it’s become too late. This usually occurs when a member of the other team is not familiar with their own team’s ropes, so here are a few extra less obvious reasons to also tape or mark the ends of your rope:

There are a lot of ropes out there with colors both different and similar alike. Choosing a unique color to distinguish your own rope from other teams’ ropes is a very common and obvious thing to do when making your purchase, but at times may still not prevent other teams from mistaking your rope for theirs and taking it down off the mountain or start using it for their own purposes before it’s become too late. This usually occurs when a member of the other team is not familiar with their own team’s ropes, so here are a few extra less obvious reasons to also tape or mark the ends of your rope: There are lots of ways to clean a rope, but not quite so many ways when you lack a washing machine, tub and/or water– especially out at the crag. Bringing along a few white rags to clean the excess dirt and dust off can be a real bonus out there. Here are a few ways!

There are lots of ways to clean a rope, but not quite so many ways when you lack a washing machine, tub and/or water– especially out at the crag. Bringing along a few white rags to clean the excess dirt and dust off can be a real bonus out there. Here are a few ways!